Medical Imaging and back pain – what does the evidence tell us?

Offshore Physio Torquay – May 2019

An issue that often presents in the clinic is the decision on whether a patient requires a scan for low back pain (LBP). Patients often already arrive with scans on their first visit either from referral from another health care practitioner or from previous onsets. Some people are very fearful of results of scans, especially of the dreaded “disc Bulge”. This fear is perpetuated via google searches, discussions with friends and family who have had back pain and sometimes even by other health care professionals. However, the evidence tells us that what we see on scans has poor correlation to the amount of pain we experience, and therefore we shouldn’t fear a disc bulge. In fact, its more common than you think in people who do not have any pain. I thought it would therefore be appropriate to discuss the evidence behind the value of imaging for LBP.

LBP is pain between the lower rib margins and the buttock crease and can occur with or without neurological referral into the lower limb. LBP is very common, affecting up to 80% of the population at some point throughout their lifetime. Therefore, it is more common than uncommon to have LBP at some point in your life. 90 to 92% of most LBP cannot be attributed to a specific structure and garners the term non- specific low back pain. The remaining presentations can be attributed to vertebral compression fractures (4%) or inflammatory spine diseases (<5%) (Wáng et.al, 2018). Less than 1% can then be accounted for by more serious underlying conditions such as infection (0.01%), Cauda equina syndrome (0.04%) and metastatic cancer (0.7%) (Wáng et.al, 2018). Signs of these more sinister presentations in the 1% of the population of LBP can be screened and monitored via physiotherapists and doctors through physical and subjective exam. It is this 1% where early imaging is vital (Wáng et.al, 2018).

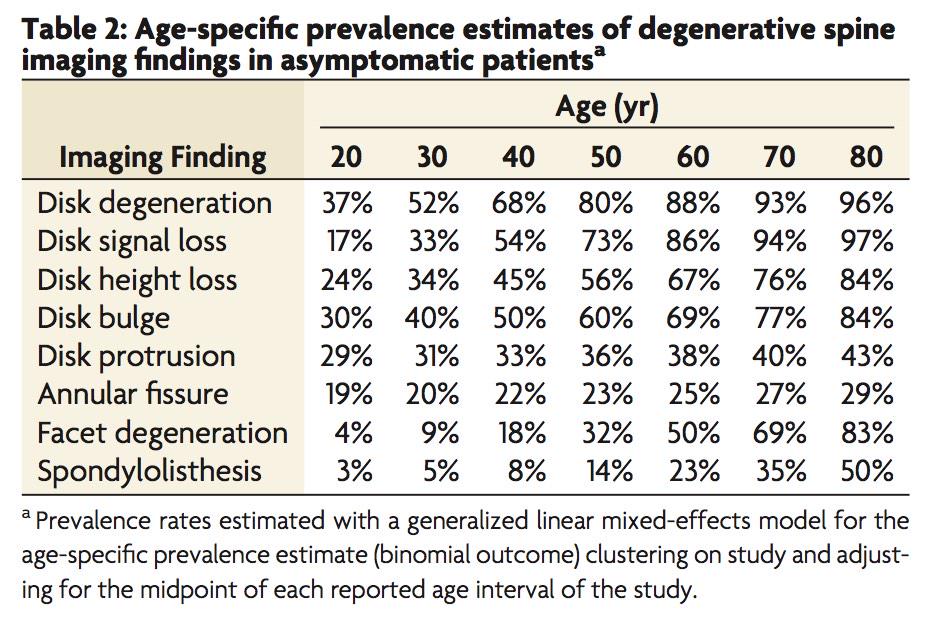

How prevalent are change such as disc degeneration, disc bulges and facet arthritis

(Brinjikji, et al., 2015, p.813)

Many people present expecting that they need a scan in order to determine appropriate treatment and enhance the chance to recover. The evidence however tells us that most of the time this is not the case (Darlow, 2017). In fact, a number of studies have shown worse outcomes in terms of pain and disability for patients who have had early imaging after LBP onset compared to those who didn’t or where blinded to the results of their scan until after the trial (Wáng et.al, 2018). Rationale for worse outcomes in these patients whom underwent early scanning may be that it produced unintended harms of diagnostic labelling, causing patients to embody these labels. These labels or clinically irrelevant findings can produce worse outcomes as it can cause the person with LBP to worry more, focus excessively on their pain or avoid exercise or return to work due to the fear of doing structural damage to their back (Wáng et.al, 2018). On top of this early scanning within a month of the onset of LBP was associated with 8 times greater risk for surgery and 5 times the amount of medical costs compared to those whom don’t undergo early imaging (Wáng et.al, 2018).

The guidelines for when to image the spine include:

- LBP and radiculopathy (neurological symptoms) for greater than 6 weeks, after failure of conservative care (Physiotherapy)

- Low back pain with severe, progressive neurological deficits (Loss of strength, power or reflexes)

- Signs of a serious or specific underlying condition (cancer, infection or cauda equina) but remember this is less than 1% of LBP presentations, however we should always be vigilant in assessing for these presentations.

Despite this there has been a significant increase in MRI scanning over the last 15 years despite guidelines suggesting routine scanning is unhelpful.

Summary

There is strong evidence that routine imaging for LBP in unnecessary and can have more negative than positive effects on outcomes in terms of pain and associated disability. This is because many changes detected are normal and poorly correlated with pain. Early imaging in these cases therefore exposes patients to an increase risk of more invasive medical interventions and can lead to worry, focus on pain, protective movement and withdrawal from exercise, social activities and work. All of which can increase pain. Essentially for the 90 to 92% of patients the findings on scanning will not change how a physiotherapist helps you to manage your pain. A major caveat however is that early scanning is vital in the 1% of the population whom may present with infection, metastatic cancer or cauda equina. Ongoing screening through history taking and physical exam for these presentations should occur by a health professional.

Ryan Dahlhaus has been a physiotherapist since graduating in 2012 from Latrobe University. He has worked at Offshore Physio since 2015 and is currently completing his Masters of Science in Medicine in Pain Management at the University of Sydney. He works with a lot of people with chronic pain to get them back and moving. If you want to discuss a chronic pain condition, Ryan works at both the Torquay and Grovedale clinic.

The information presented in this summary is from three main academic articles links to the full text are provided as all are open access papers:

Brinjiki W, Leutmer PH, Comstock B, et.al, (2015). Systematic literature review of imaging features of spinal degeneration in asymptomatic populations. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2015; 36 (4):811-6 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4464797/pdf/nihms-696022.pdf

Darlow, B., Forster, B., O’Sullivan, K., & O’Sullivan, P. (2017). It is time to stop causing harm with inappropriate imaging for low back pain. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 51(5), 414–415. https://bjsm.bmj.com/content/51/5/414.long

Wáng, Y., Wu, A., Ruiz Santiago, F., & Nogueira-Barbosa, M. (2018). Informed appropriate imaging for low back pain management: A narrative review. Journal of Orthopaedic Translation, 15, 21–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jot.2018.07.009